A Monster of a Novel: Walter Dean Myers

Monster and its challenges; why librarians fight for it; and other book ban news

The following post is part of a Seed Pod collaboration about libraries. Seed Pods are a SmallStack community project designed to help smaller publications lift each other up by publishing and cross-promoting around a common theme. We’re helping each other plant the seeds for growth!

Next week, for the official Banned Books Week, I’d like to look at a more recent author, Akwaeke Emezi, whose BIPOC queer characters include transgender youth. This week, I’d like to finish my discussion of books that have been repeatedly challenged over decades and sometimes removed from library collections.1

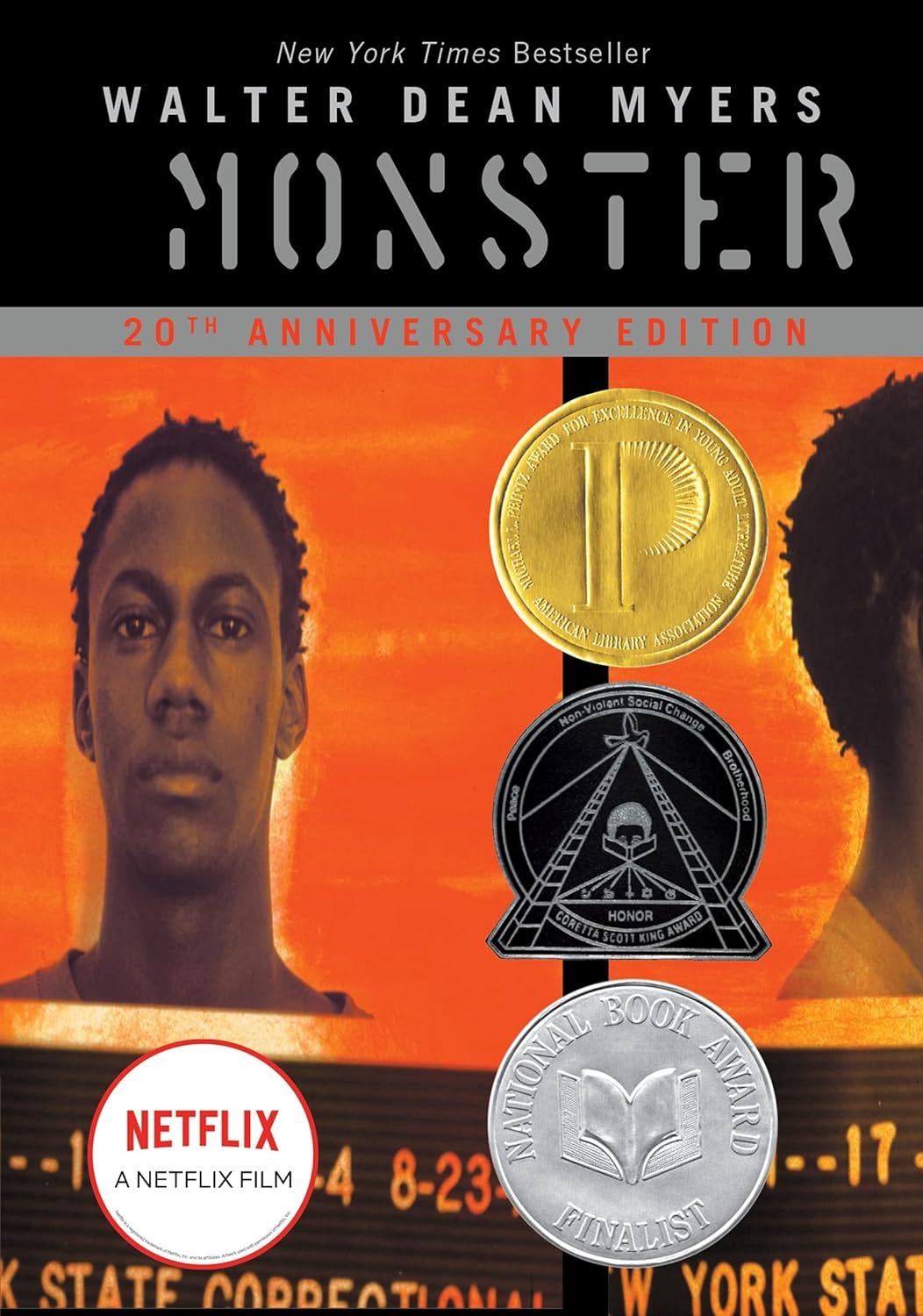

Walter Dean Myers’ Monster

Monster was nominated for the 1999 National Book Award for Young People's Literature, won the Michael L. Printz Award in 2000, and was named a Coretta Scott King Award Honor the same year.

When I was working on last week’s post about Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak and Shout, I was reminded of how grateful I am to Walter Dean Myers for his YA novels and his memoir, Bad Boy. Halse Anderson met Myers at the National Book Award ceremony in 1999. She was there for Speak, he for Monster.2 When it was time to go to lunch, Myers was talking to a reader. As Halse Anderson writes in Shout:

Walter was the first established author I’d met

he welcomed me into the world of books for kids

with joy, wisdom, and grace, he taught

me everything I know about my responsibility

to my readers, starting that day

Cuz he didn’t go to lunch at all, he waved us off

that young man was filled with questions

and Walter had some answers

and questions of his own

he made the time for a reader

because integrity required it

that’s what we’re called to do (171)

I love this because it shows Myers is the person we hope for. His books have been widely read for decades. His work was very popular in my libraries and we owned multiple copies of each. Like Speak, Monster is a novel that has stood the test of time. Let’s consider why people want to remove it and what it is that makes school librarians want to keep it in their collections.

Monster

The main character of Monster, Steve Harmon, appears to be a good guy in general—he has no criminal record, and he’s a talented cinematographer. Yet somehow he has gotten involved with other guys who are arrested for murdering a Harlem drugstore owner. Accused of being the lookout for this robbery gone wrong, Steve, at sixteen years old, is on trial for that drugstore owner’s murder.

The story is told through Steve’s journal entries and through a screenplay he is writing about his experience. The journal gives the reader insight into Steve’s experience in jail and his feelings about his experience. Steve’s screenplay is more objective—people speak for themselves—lawyers, the four accused boys, the officers, the judge. The truly interesting thing about this format is that it is not clear whether Steve has willfully participated in the drugstore robbery. As you read and try to figure it out for yourself, you’ll be swayed by the evidence, by your sympathy for Steve and his parents, and by your own experiences with the law and prejudice/racism (Steve is Black)—whatever those experiences are.

Common Sense Media has good things to say about Monster and rates the novel as appropriate for ages 13 and above, thus appropriate for high school libraries. They add this warning: “There is some gritty material: characters are beaten up, the rape of inmates is implied, and Steve is terrified of being sent to prison.”

My own feeling about Monster when I read it in 2008 was that it was a cautionary tale. I understand this might not be what another reader gets out of it. That’s the power of Monster—it leaves the reader to think and decide. Having to do so is important for students, particularly at the high school level. Monster makes for great classroom discussions on the justice system, racism, and the small steps that can lead to arrest.

Monster was used as supplementary reading in our district. At least once, a parent complained about it to the school board, believing it promoted criminal behavior. The superintendent called me to ask about it. The book wasn’t removed. (However, what sometimes happens in these cases is that the teacher is tired of fighting and stops using the book if it isn’t required. It’s a form of self-censorship that results from book challenges.)

Monsters in the library

In 2020 (21 years after the publication of Monster) Spencer Miller wrote in a Bookstacked article, “The excuses used to silence Black authors,” that he believes the continuing objections to the novel are due to a desire to look the other way on the issue of racism and to silence the messages of Black authors, especially since the death of Trayvon Martin at the hands of George Zimmerman in 2012.

“In 2013, Monster (1999) by Walter Dean Myers — a classic and award-winning YA novel often taught in American schools — was challenged by a small group of parents in Illinois who objected to the novel being taught in their children’s classroom” for ‘mature content.’

Many of these books, such as The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas and All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely, have received national acclaim and attention and have even been adapted or optioned for film. “This isn’t a literary trend. This is an issue of our time,” said Jason Reynolds. … There have been widespread attempts made to silence these Black authors and remove their books from the shelves of schools and libraries and out of the hands of young readers. … A complaint is registered about a book’s “mature themes,” not that it is a story about a young African American on trial by an unjust justice system.

I encourage you to read the entire article, which discusses the books mentioned in the above paragraph, novels more recent than Monster (published in 2017 and 2015).

Why librarians keep Monster

Monster remains in the library because discussion of issues of racism and of the lives of people of color are important parts of the schools’ mission to encourage both critical thinking and empathy.

Myers himself addressed efforts to ban the book in an interview with the National Coalition Against Censorship in 2013.

“I think that most often the people wanting to censor books are well-meaning and concerned about the welfare of their children,” he said. “But I suggest that children will be exposed to the world in spite of their efforts, and that exposure is best handled in a school setting.” 3

I’ve read several of Myers’ books because they speak to and from Black experience. They’re great for reluctant reader guys who come to the library only because their teacher requires them to check out books. (This was often the case with reading classes; those classes were a requirement only for students who are years behind on reading levels.) Once they read Myers, they would go straight to his place on the library shelves and pick another. So—Myers creates readers and thinkers. That’s why I had his books (and why I had books like The Hate U Give and All American Boys). I wrote reviews about some of Myers’ books that you might want to pick up for a teen in your life:

Bad Boy: A Memoir (Myers’ youth)

Fallen Angels (Vietnam War soldier)

Game (high school basketball player)

Shooter (school shooting)

As well as Monster.

Part 2

Libraries challenged and banned book news

The Secret Life of Librarians from the Carnegie Corp. of New York (Super feel good! This is one that will make you happy!)

In partnership with the American Library Association and the New York Public Library, Carnegie Corporation of New York celebrates ten exceptional librarians every year with the I Love My Librarian Award. The 2024 honorees were chosen from a pool of more than 1,400 community-based nominations and were each awarded a $5,000 prize in recognition of their exceptional public service.

The Secret Life of Librarians explores their unexpected stories and contributions as civic heroes who improve lives and bring communities together.

Florida county restoring dozens of books to school libraries after ‘book ban’ lawsuit from Politico

The county settled a federal lawsuit with a group of parents, students and the authors of a removed book.

TALLAHASSEE, Florida — A central Florida school district this week agreed to restore 36 books that were challenged and previously pulled from campus libraries in a settlement of a federal lawsuit fighting how local officials carried out the state’s policies for shielding students from obscene content.

The settlement reached by Nassau County school officials and a group of parents, students and the authors of the removed children’s book “And Tango Makes Three” marks a significant twist in the ongoing legal battles surrounding Florida’s K-12 book restrictions, which have been derided as “book bans” by opponents. Under the agreement, that book and others such as the “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison and the “The Clan of the Cave Bear” by Jean Auel will once again be available to students after being removed last year.

With A Spiking Crisis of School Book Bans, PEN America Draws Writers, Readers and Advocates Together to Champion the Freedom to Read From PEN America

This year, PEN America’s preliminary documentation of book bans is showing a dramatic increase in books removed from school classrooms and libraries– over 10,000 instances of bans during the full 2023-2024 school year (July 2023-June 2024), with Florida and Iowa at the front. Researchers expect this number—more than twice over the previous school year— will rise even higher as the count approaches its final stage before release later this fall. This wave of censorship targeted books from biographies and history books to young adult novels and picture books. In a heightened tactic of censorship, PEN America found that increased hyperbolic rhetoric about “porn in schools” was used to justify banning books about sexual violence, LGBTQ+ identities, and books by women and nonbinary authors.

ACLU Fights Government Censorship of Books in Texas Public Libraries

ACLU and ACLU of Texas file amicus brief urging the Fifth Circuit to protect access to books in public libraries

DALLAS — The American Civil Liberties Union and the ACLU of Texas filed an amicus brief today in Little v. Llano County, urging the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit to protect the public’s right to access diverse books and ideas at public libraries. This will be the first time an appeals court will decide what First Amendment standard governs the removal of books from public library shelves.

“If courts allow government officials to pull books out of public libraries in order to impose a government-approved set of views, they're opening a Pandora's box of censorship,” said Vera Eidelman, staff attorney with the ACLU's Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project. “We're urging the Fifth Circuit to recognize that allowing politically-motivated book removals would fundamentally distort the nature and function of public libraries.”

Are censorship and lack of challenging books factors in why your teen can’t read? | Opinion from the Kansas City Star

The winner that year-1999–was When Zachary Beaver Came to Town. I read it in 2008 and wrote this review at that time.

https://www.wric.com/news/local-news/henrico-county/henrico-school-board-rejects-parents-book-ban-request/

Always helpful and informative -- l especially appreciate hearing about these YA books, with which I'm not very familiar. And want to be! Thank you!