Don’t be a “Cub Scout of White Supremacy” (Celebrate your Library!)

Banned books; Me and Earl and the Dying Girl; Perks of Being a Wallflower; Carrie; Rabbit Hole; sociopaths in fiction

We’re finishing up National Library Week! (Last week we had School Librarians’ Day.) Since we’re still celebrating libraries and librarians, I want to flip the script and discuss libraries and book challenges first and foremost in this post.

The top ten challenged books in 2023

ALA Releases Top 10 Most Challenged Books of 2023

The Most Challenged Books of 2023

1. Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe, for LGBTQIA+, and sexually explicit content.

2. All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson, for LGBTQIA+ and sexually explicit content.

3. This Book Is Gay by Juno Dawson, for LGBTQIA+ and sexually explicit content.

4. The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky, for LGBTQIA+, and sexually explicit content, rape, drugs, profanity.

5. Flamer by Mike Curato, for LGBTQIA+ and sexually explicit content.

6. The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, for rape, incest, sexually explicit and EDI (equity, diversity, inclusion) content.

7. (Tie) Tricks by Ellen Hopkins, for LGBTQIA+ and sexually explicit content.

7. (Tie) Me and Earl and the Dying Girl by Jesse Andrews, for sexually explicit content, profanity.

9. Let’s Talk About It by Erika Moen and Matthew Nolan, for LGBTQIA+ and sexually explicit content.

10. Sold by Patricia McCormick, for sexually explicit content, rape.

This list is posted in many places (the link above is to Publishers Weekly), but in his Book Club newsletter for the Washington Post, Ron Charles reminds the reader:

You can probably divine a pattern in this list. According to the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, almost half of the 4,240 titles challenged in 2023–“ a record high, by the way— “were by or about people of color or LGBTQIA+ individuals. Book censors drunk on lurid fantasies of depraved librarians and pedophile school teachers are the Cub Scouts of White supremacy, part of a larger effort to bleach our understanding of American society and to label whole groups of people fundamentally obscene.

I’ve been shouting this to readers in articles and posts for the last few years, but Charles has a way with words! (“Cub Scouts of White supremacy”—!!!)

I reviewed a few of these ‘most banned’ books back when they were new and I was a teacher librarian. My review of Me and Earl and the Dying Girl begins:

There really is a dying girl in this novel, so to say that most of it is a lot of fun seems weird. But it is fun. You should read it.

My review of The Perks of Being a Wallflower is a shorter one (where I was trying not to give away a major reveal in the book). I end with:

Despite the strikes against him, Charlie befriends a small group of misfits—and the novel makes clear that just about everyone in high school is a misfit, even the most popular cheerleaders and football stars. Though Perks has been compared to The Catcher in the Rye, partly because it deals with teen depression, the subject matter is more contemporary—the characters must deal with current sexual attitudes, parties and drugs, date rape and teen pregnancy. Not that they don’t have fun—some of the most poignant passages in the book are on how carefully Charlie chooses gifts for his friends, how well he ‘reads’ their hearts and how much he loves them, and receives love in return. This is a truly engaging and honest book for mature readers.

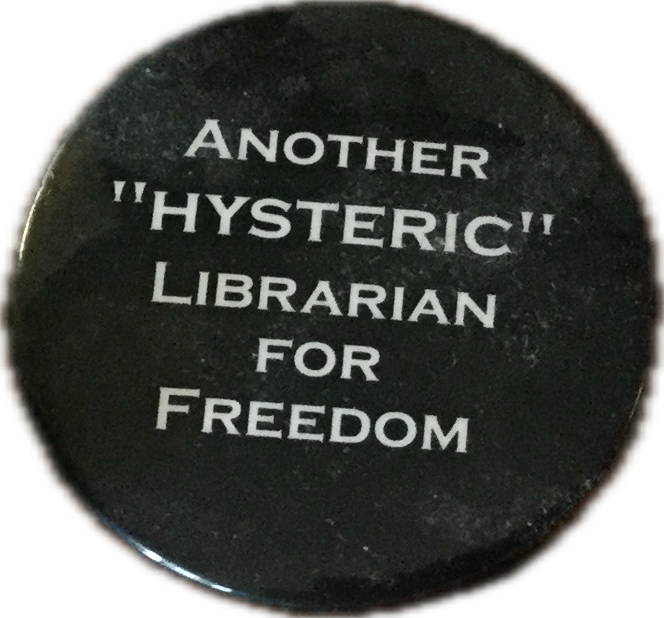

So I guess this places me in league with all the other ‘depraved librarians and pedophile school teachers’ (yes, I also taught English for a dozen years!) My offenses were serious. Not only did I positively review YA books online, I bought multiple copies of many such titles and ‘booktalked’ them. Classes came into the library with their teachers and I’d have about five copies of each of five titles for each class. I’d tell them why I liked the books. Then they’d check out any book in the library they wanted, but all the copies of all the titles I chatted up were always the first to go. Teens would rush the book display to grab them once I was finished with my presentation. Once, a boy leaped over a desk and threw himself at the display to grab a book before other students could get to it.

As I’m not actually depraved or a pedophile, this is what I was really doing:

Getting the right book into the hands of the right reader at the right time

Encouraging a practice of reading for pleasure (i.e., not just because a book is required). That is, planting the seeds for students to become lifelong readers.

These are pretty positive things to do. I once ended an article on book censorship with “Read widely! Read wildly!” This is my motto.

Here’s an excerpt of that article (Censoring Books Means Censoring Empathy)

“Kirkus” called “Bitter” (2022) by Akwaeke Emezi “A compact, urgent, and divine novel.” The protagonist studies at a school for creatives. Through her artwork, she joins students from a nearby school to protest social injustice. In doing so, she unleashes an avenging angel who causes damage and death.

The characters are, generally, Black and queer. Their desire for social justice serves as an entry to discussion about the subject. “Bitter” also engenders conversation about the role of creatives and their contributions to society. It would be a great teen book club choice. It’s a prequel to “Pet,” which is on Texas’ list of suspect books.

Access to such novels provides teens the opportunity to develop a trifecta of life skills: compassion, imaginative thinking, and the ability to analyze and evaluate ideas. As Barbara Kingsolver noted, “Fiction has a unique capacity to bring difficult issues to a broad readership . . ., creating empathy in a reader’s heart for the theoretical stranger. Its capacity for invoking moral and social responsibility is enormous.”

A vocal minority can keep marginalized students from books that validate their lives. The same minority can keep all teens from accessing novels that empathize with historically underrepresented people. As a parent who raised thoughtful readers, I can’t imagine allowing other parents to make that choice.

This week’s book challenge news

Unite Against Book Bans expands book resume collection for National Library Week

Unite Against Book Bans launched the book resumes resource in February. Created in partnership with dozens of publishers and with information provided by publishers, librarians, and School Library Journal, these easy-to-print documents are designed to help support access to books that are targeted by censors. Each book resume summaries the book’s significance and educational value, including a synopsis, reviews from professional journals, awards, accolades, and more. When possible, the book resumes also include information about how a title has been successfully retained after a demand to censor the book.

'It's Been Devastating': A Q&A With The Top Librarian Fighting The GOP's Book Bans "The weaponization of libraries ... is a bludgeon that’s scaring people everywhere," said American Library Association President Emily Drabinski.

When you fund libraries, you have more things that the library funds in the community. What gets lost in conversations about book banning is that it’s really about eliminating the institution of the library, period. It’s not about the books. Well, it is about the books, but the books are the way in to gut one of the last public institutions that serves everyone.

How SPL’s Books Unbanned card is fighting censorship

[Brooklyn Public Library] founded the Books Unbanned program in 2022 to combat that censorship by expanding digital access to its collections to U.S. youth. Since [Seattle Public Library] joined the program in 2023, more than 8,000 young people across the United States signed up for a SPL Books Unbanned card to check out a range of books, including titles banned or censored in their own communities. So far, cardholders ages 13 to 26 have checked out 137,000 digital books, according to SPL representatives. (SPL’s program is privately funded by The Seattle Public Library Foundation.)

What I’m watching: films based on books about sociopaths

Have you been watching the new Ripley on Netflix?

I watched the entire season of Ripley on Netflix, yet another take on Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley. It was so very good for pacing and cinematography and of course, for the story itself and the creepy nature of Tom Ripley. For an almost unbelievable nightmare true story of identity theft, check out this article in the LA Times this week.

He lost identity, then freedom After William Woods’ ID was stolen in the ’80s, he spent nearly 2 years in jail and a psychiatric hospital. Now he might sue the city of L.A.

I also watched Zone of Interest on Max, a fictional account of the lives of Rudolph Höss, his wife and family as they lived just outside the Auschwitz death camp. It’s based on the novel by Martin Amis. While Ripley and Zone are very different programs, they’ve increased my interest in the dark triad personality, a topic I’d like to explore in a post. I previously explored the idea that evil people have typical human traits. That novel antagonists can’t be villains. But I’m starting to think that more people have sociopathic personalities than we know.

Revising Villains

The traits of a villain, the traits of an antagonist I have writer friends who believe the universe will align with their desires, that they manifest their success. I’m not any good at manifesting success for myself or any of my loved ones, but when small things come together to inspire me, I’m grateful. That happened this week as I tried to turn my vill…

More 50 years of Carrie

If you’re still celebrating 50 years of Carrie, you might enjoy Margaret Atwood’s take on its popularity: Stephen King’s First Book Is 50 Years Old, and Still Horrifyingly Relevant. (This is another gift link from me to the NYT article, so you should be able to read the entire article for free.)

But underneath the “horror,” in King, is always the real horror: the all-too-actual poverty and neglect and hunger and abuse that exists in America today. “I went to school with kids who wore the same neckdirt for months, kids whose skin festered with sores and rashes, kids with the eerie dried-apple-doll faces that result from untreated burns, kids who were sent to school with stones in their dinnerbuckets and nothing but air in their Thermoses,” King says in “On Writing.” The ultimate horror, for him as it was for Dickens, is human cruelty, and especially cruelty to children. It is this that distorts “charity,” the better side of our nature, the side that prompts us to take care of others.

I think this is part of King’s widespread appeal. Yes, he shows us weird stuff, but in the context of the actual. The clock, the sofa, the religious paintings on the walls—all the daily objects that Carrie explodes during her rampage—these are drawn from life, as is the everyday sadism of the high school kids that makes “Carrie” feel as frighteningly relevant as ever.

What I’m Reading

Rabbit Hole by Kate Brody: Mistakenly advertised as a thriller, this is more a book about long grief over a (probably murdered) missing sister and the effect that her disappearance has on the family and community. In that it includes amateur sleuths, it reminds me of I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai. However, the sleuths in Rabbit Hole include doxxers and misogynists and those pushing back against them. This brings up a different set of questions for the reader, the answers to which don’t solve the likely murder.

As you might imagine, I loved pitching books!

I love imagining your teenage patrons leaping over desks to be the first to read a book. Sounds like you were great at pitching!